📦 Defining Category Defining Companies

It's much easier to win the race when you're creating the rules.

Some companies become so legendary that even people outside of their industry know their names. They are not just good businesses. They are the companies that define the space they operate in. They are first in class, or best in class, and they set the bar for everyone that comes after them.

These companies are worth studying closely because they don’t just win in their markets. They create the markets. They endure ankle-biting competitors and come out stronger. They become the mental model for how that category should work.

What does it take to build one? The pattern is surprisingly consistent. Category defining companies require three things:

Choosing a nascent or risky market

Relentless execution on product and go-to-market

Good timing, often helped by luck

Each by itself is not enough. Together they create the rare outcome where a company can become the default.

The Three Ingredients

Market Choice

Category defining companies almost always begin in markets that look too small, too weird, or too risky. At the start, these markets are dismissed by incumbents and ignored by most investors. That is exactly the opportunity. By the time others realize the space matters, the category leader has already been established.

Execution Compounds

The companies that win execute better than anyone else. Their product is 10x better, their go-to-market motion is tuned to the way their category buys, and their culture is focused on speed and iteration. Execution is where the advantage compounds.

Being Early vs Being Ready

Even with the right market and great execution, timing matters. Many of these companies looked too early at the start. What made the difference is that they survived long enough to be ready when the wave hit. Along the way, each got lucky with a break that gave them credibility or scale at a critical moment.

Five Category Definers

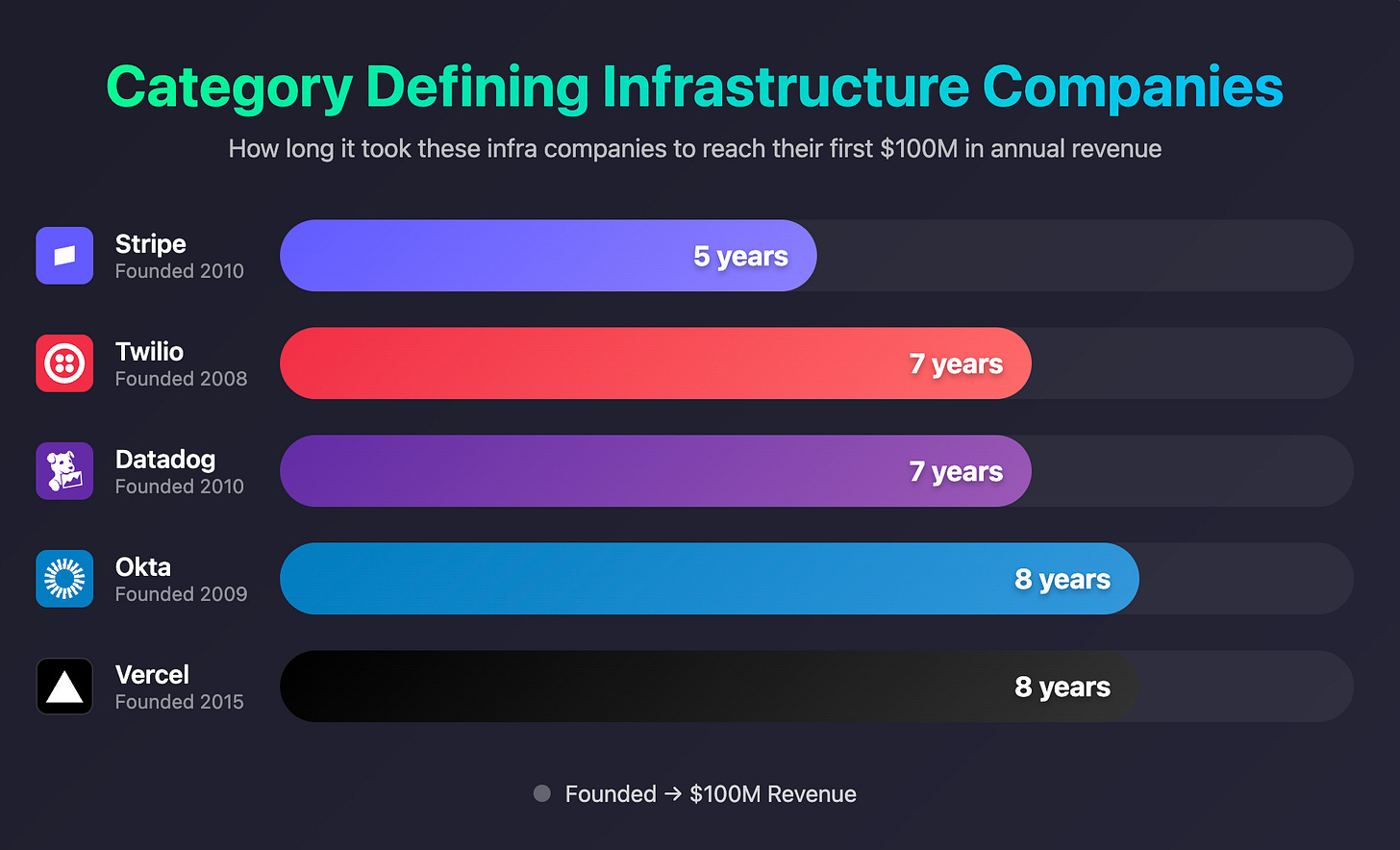

Twilio: Turning Telecom into Software

When Jeff Lawson founded Twilio in 2008, the idea that a startup could disrupt telecom seemed absurd. The industry was dominated by carriers and hardware vendors. Developers had almost no ability to add communication features into software.

Twilio changed that. Jeff’s insight was that communications could be abstracted into APIs. Instead of cutting deals with carriers or wiring up hardware, a developer could add a few lines of code and instantly send texts or make calls. It was a risky bet on a market that technically didn’t exist yet: communications-as-a-service.

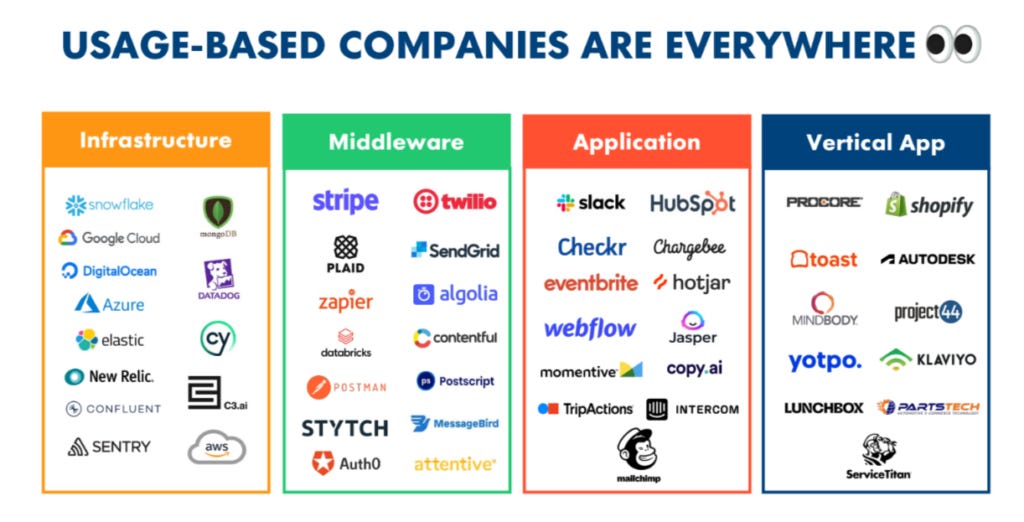

Twilio focused on developers, not IT buyers. The APIs were simple, the pricing was usage based (which was unique), and the documentation was excellent. “Ask Your Developer” became more than a slogan. It was the strategy. Developers adopted Twilio in droves, and companies like Uber built critical features on top of it.

The smartphone and app boom created massive demand for embedded communications. Twilio was ready, and by the time the world caught up, it was the default. By 2018 Twilio had crossed $500 million in revenue and effectively defined CPaaS as a category.

Stripe: Payments for Developers

Stripe became famous for one thing: seven lines of code to accept a credit card. A developer could copy-paste those lines and start taking payments instantly.

Patrick and John Collison built Stripe in 2010 to fix a broken system. Online payments meant bank paperwork, clunky gateways, and confusing APIs. PayPal worked, but it pulled users into its own flow and was never designed for developers.

Stripe changed that with an API that worked out of the box. The pricing was transparent, and the focus on developer experience was relentless.

The growth motion mirrored Twilio: bottoms up and product led. Startups could adopt Stripe instantly, without sales calls or integration consultants. As those startups grew, Stripe scaled with them. Over time it expanded into subscriptions, marketplaces, and fraud prevention, building a broad payments platform.

Just as SaaS and e-commerce were breaking out, Stripe had the rails in place. Every new company wanted it. Stripe hit the milestone years faster than peers, crossing $500 million in revenue soon after 2016. Today it is the defining brand in developer-first payments.

Vercel: The Frontend Cloud

Deploying a modern web app used to mean wrangling servers, CDNs, and pipelines. Guillermo Rauch saw that frontend developers were underserved and decided to fix it.

He founded Vercel (fka ZEIT) in 2015 and chose an overlooked market. The strategy was a one-two punch: build the open-source framework Next.js and pair it with a cloud platform tailored for it. Every pull request got a preview URL, deployments were instant, and global edge distribution just worked.

Next.js solved real problems with React, like server-side rendering and routing. Its adoption spread quickly, creating a natural funnel to Vercel’s platform. Freemium entry and enterprise upsells gave the company a scalable model.

When React surged and SEO pressures pushed developers back toward server-side rendering, Next.js was waiting. By 2023 Vercel had scaled past $100M ARR and set the standard for the frontend cloud.

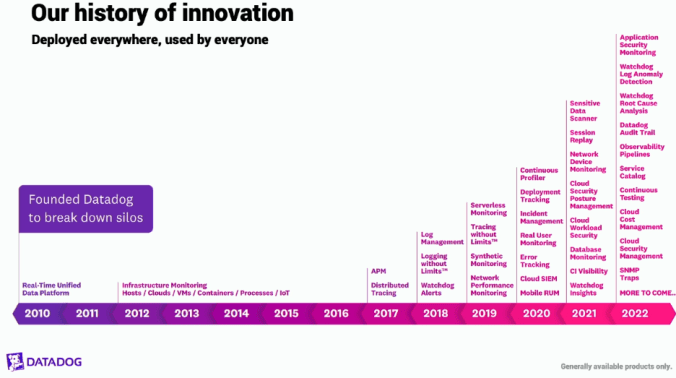

Datadog: Observability for the Cloud Era

When Olivier Pomel and Alexis Lê-Quôc founded Datadog in 2010, most people still thought of the cloud as a toy. Enterprises ran their workloads on-prem and monitoring was handled by legacy tools like Nagios, Splunk, or New Relic. Investors told them it was too early.

They were early, but they were right. Datadog’s insight was that DevOps teams would need a single place to see infrastructure, application traces, and logs as they moved to cloud. A simple metrics collector, hundreds of integrations, and a SaaS delivery model gave customers immediate value. From there Datadog kept expanding into APM, logs, and security.

Its GTM model combined free trials and bottom-up adoption with a sales team to land enterprise deals. Pricing scaled with usage, which aligned perfectly with the growth of cloud workloads.

Cloud adoption hit an inflection point in the early 2010s, and Datadog was one of the only companies ready with a mature product. A lucky break was surviving the lean years with just enough capital until the wave hit. By 2020 Datadog had passed $500 million in revenue and was the clear category leader in observability.

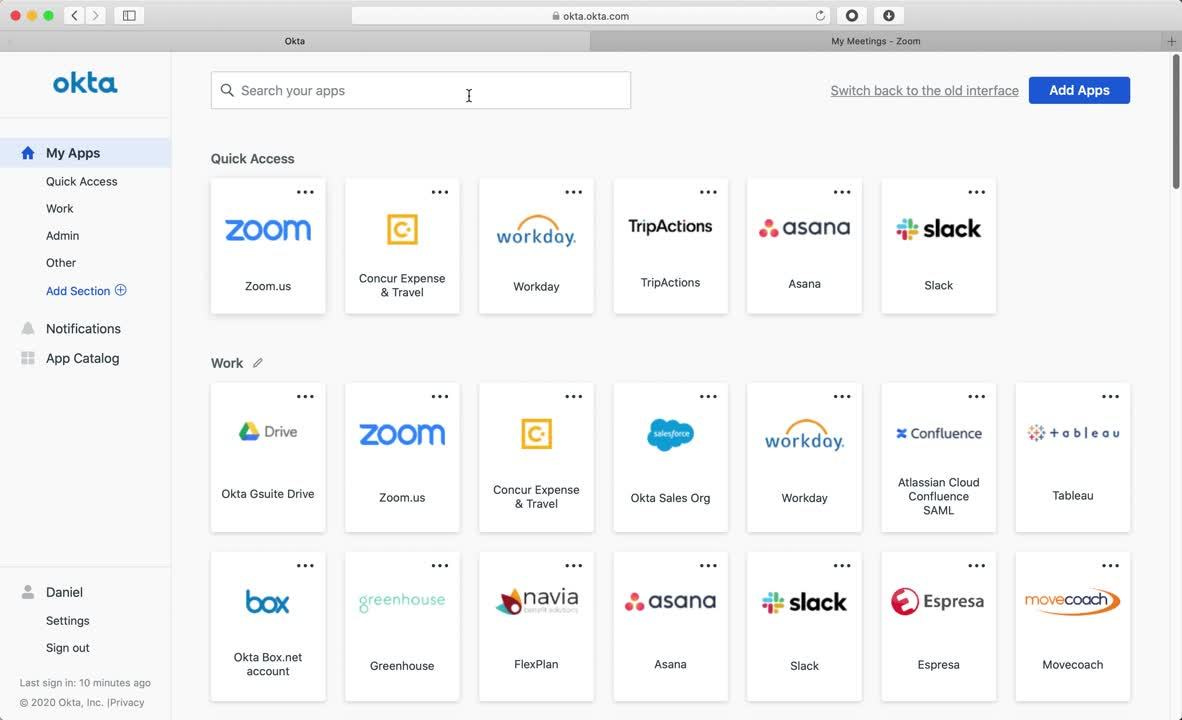

Okta: Identity in the Cloud

In 2009 Todd McKinnon quit Salesforce to build cloud identity. Even his wife thought he was crazy. At the time, enterprises used Microsoft Active Directory, Oracle, or IBM for identity, all tied to on-prem systems. A cloud alternative sounded impossible.

Okta executed by focusing entirely on identity-as-a-service. They spoke with dozens of CIOs to validate the pain, then built a platform that was reliable, secure, and easy to integrate. The Okta Integration Network gave IT teams pre-built connectors to thousands of apps.

Unlike Twilio or Stripe, Okta’s GTM was top down. Identity decisions are made by CIOs and CISOs, so Okta invested early in enterprise sales and support. It wasn’t fast. Okta took years to find product-market fit. But once it did, the trust it had built with enterprises paid off.

SaaS adoption was exploding, and companies suddenly had dozens of apps to manage. Okta became the neutral identity layer they needed. A lucky break came with early reference customers like Netflix. By 2019 Okta had passed $500 million in revenue and cemented itself as the category-defining company in cloud identity.

How They Won in Different Ways

When you zoom out across Twilio, Stripe, Vercel, Datadog, and Okta, you see sharper contrasts in how they each became category defining. The companies followed the same broad pattern (risky market, great execution, right timing) but the way they played the game was different.

Developer-Led vs Enterprise-Led

Twilio and Stripe are the purest examples of developer-led growth. Both built APIs that made complex infrastructure simple, and both went straight to the individual developer. Their products were self-serve, their pricing was pay-as-you-go, and their growth came from bottoms-up adoption. Twilio got embedded into apps like Uber without a central IT decision. Stripe became the default choice for startups spinning up online payments. In both cases, developers had the power to choose, and Twilio and Stripe gave them superpowers.

Datadog started bottom-up as well, but its market forced a hybrid motion. Monitoring often starts with a single team but quickly becomes an enterprise-wide need. Datadog had to layer on a sales force to close large deals. Its brilliance was in keeping the developer experience simple enough for bottoms-up adoption while investing in enterprise sales at the right time.

Vercel is another variant. Like Twilio and Stripe, it focused on developers, but its strategy hinged on controlling an open-source framework. By creating Next.js and then offering the best platform to run it, Vercel built a funnel that was both grassroots and product-led. That gave it a different kind of leverage. Developers adopted Next.js for free, and a significant percentage naturally flowed to Vercel.

Okta sits apart. Identity is not something developers pick in a hackathon project. It is a CIO-level decision about security and trust. Okta had to be enterprise-first from day one. That meant a heavier sales motion, longer sales cycles, and years of building credibility. It looked slower, but once Okta broke through, the stickiness of identity created a massive moat.

What They Displaced

Each of these companies defined their category by displacing entrenched incumbents. But the shape of the incumbents was different.

Twilio went up against the telecom carriers and legacy contact-center vendors. These were slow-moving giants with no cultural affinity for developers. Twilio reset telecom by turning it into software.

Stripe displaced PayPal, Authorize.net, and the banks. The incumbents were technically capable but architecturally outdated. Stripe outpaced PayPal by giving developers APIs that actually worked.

Vercel replaced the DIY approach of piecing together AWS, CDNs, and CI pipelines. It also competed directly with Netlify. Vercel won by integrating an open-source framework with a cloud platform, which no one else had done.

Datadog unified categories that had been split across multiple tools. It pulled usage from Nagios, Splunk, New Relic, and a dozen other incumbents. Datadog unified what others kept siloed.

Okta replaced on-prem identity systems like Active Directory Federation Services and Oracle IAM. These systems were not built for cloud apps. Okta redefined identity by being neutral and cloud-first.

The contrast here is important. In some markets, the incumbents were slow and complacent. In others, they were simply mismatched to the new environment. What all five companies had in common is that they saw an opening to create a new standard that incumbents were too slow or too stubborn to meet.

Go-to-Market Fit

A critical piece of execution was aligning go-to-market with the way the market actually buys. This is where the companies diverged.

Twilio and Stripe thrived on self-service and usage-based pricing because developers could buy without approval.

Datadog needed a hybrid because observability starts small but becomes a C-level purchase.

Vercel leaned into open source as the entry point and used freemium to capture the long tail while landing enterprise contracts.

Okta built an enterprise sales machine because there was no other way. CIOs had to sign off.

This shows that there is no one-size-fits-all GTM model. What matters is the fit. Each company picked the model that matched its category and executed it relentlessly.

What They All Got Right

Despite the contrasts, there are a few themes that run across all five. These themes are what make them category defining.

Correctly Early

Each company looked too early when it started. Twilio was building cloud telecom before most developers trusted APIs for core features. Stripe was fixing payments in a world where PayPal seemed good enough. Vercel was betting on frontend infrastructure before most companies saw it as a bottleneck. Datadog launched when cloud adoption was still questioned. Okta pitched cloud identity before CIOs were ready. They had time to build, refine, and be ready when the market caught up.

10x Product Advantage

Category defining companies are driven by product quality and low barriers to entry. Twilio made telecom programmable. Stripe made payments copy-paste simple. Vercel made deployment instant. Datadog made monitoring unified and real time. Okta made identity secure and cloud-first. The product wasn’t marginally better. It set the new standard.

Developer Empowerment and Trust

Four of the five companies empowered developers directly. They gave individual engineers leverage to make decisions and ship faster. The fifth, Okta, won by creating trust at the enterprise level. Different audiences, same principle: put power in the hands of the user that matters most.

Consumption-Based Growth

Twilio, Stripe, Datadog, and Vercel all built pricing models that scaled with usage. Customers started small and paid more as they grew. This created natural net retention and made expansion built-in. Even Okta, with a seat-based model, grew as companies added more apps and more users. Growth was baked into the model.

Surviving the Desert

Each company had a desert period where the market wasn’t ready, investors weren’t interested, and growth was slow. Twilio pre-Uber, Stripe before e-commerce took off, Vercel before SEO pushed server-side rendering, Datadog before AWS hit escape velocity, Okta before CIOs trusted cloud. What made them category defining is that they survived, and were still standing when the wave arrived.

A Playbook

Category defining companies share a playbook.

Pick the market others dismiss. Twilio picked telecom APIs, Stripe picked developer payments, Vercel picked frontend hosting, Datadog picked cloud monitoring, and Okta picked cloud identity. Each market looked small, unproven, or impossible. Each grew into a massive category.

Execute relentlessly. They built products that were radically better, not marginally better. They matched their go-to-market motion to their market. They obsessed over their core user. Execution was not just about speed but also discipline and focus.

Align pricing to customer growth. Usage-based or consumption pricing aligned their growth with the customer’s success. Expansion was natural. Retention was high. The business models scaled with the market.

Be early, then endure. All five companies looked too early when they started. But being early gave them a head start. The hard part was surviving the years when no one cared. Each found a way to cross the chasm, and was ready when the market arrived.

Take the lucky breaks. Uber made Twilio famous. Shopify boosted Stripe. React boosted Vercel. Cloud inflection boosted Datadog. Netflix validated Okta. These breaks weren’t controllable, but they were only useful because the companies had already done the hard work and doubled down when the opportunity struck.

The Next Category Definers

Defining a category is not about being first. It is about being the company that shows the world how the category should work. Twilio, Stripe, Vercel, Datadog, and Okta each did that. They chose risky markets, executed at the highest level, and rode the wave of timing and luck when it came.

The next category defining company will look just as contrarian at the start, until they become the default.