⚙️ Your margin is my opportunity

Consequences of being COGS

As interest rates tick up, everyone is looking for ways to tighten their belt. Especially internet businesses. For many CFOs, this means pulling back the curtain on their financials, reducing expenses, and increasing their margins.

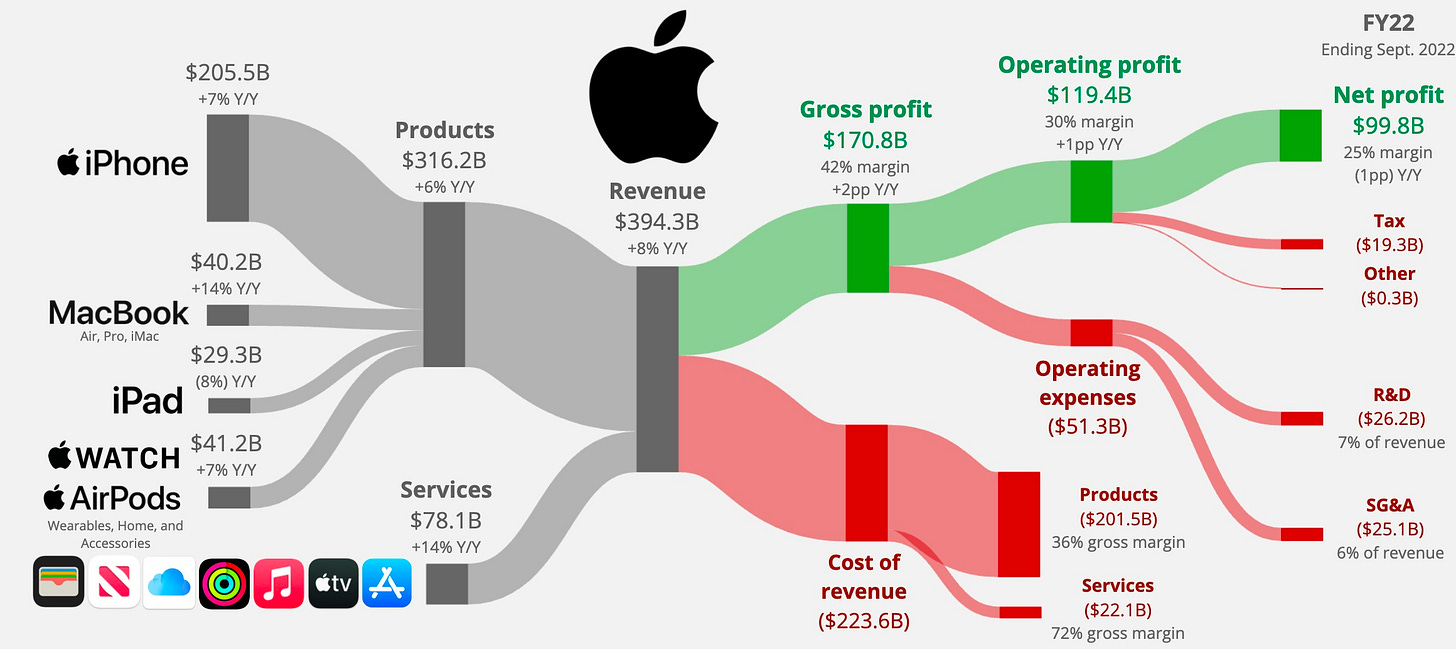

As a quick refresher, there are three types of margin: Gross, Operating, and Net.

Gross Margin: The ratio of revenue to the direct costs (Cost of Revenue) associated with producing what you sell. It's a gauge of your unit economics.

Operating Margin: The percentage of revenue remaining after covering operating costs (OpEx), serving as an indicator of your business's operational efficiency.

Net Margin: The proportion of revenue that remains as profit after accounting for all expenses, taxes, and interest, providing an overall measure of business profitability.

The allure of internet businesses has always been their ability to maintain high (90%+) gross profit margin. Each incremental customer does not require writing incremental code, and the same product can be sold to millions of customers over and over again.

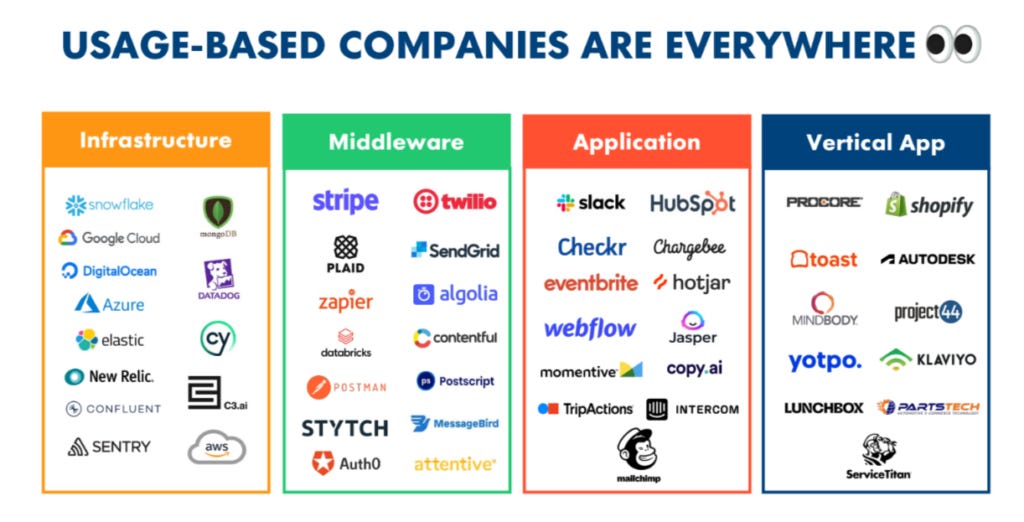

Yet, a significant change is now challenging this lucrative landscape for internet businesses: the rise of usage-based billing, which charges customers based on their actual consumption rather than a flat subscription or per-seat fee.

Now, there isn’t anything inherently wrong with usage-based billing. The problem lies in where it exists on a company’s income statement. If it’s a cost-of-revenue (COR), it becomes a flat tax on gross profit.

In the current climate, CFOs are particularly obsessed with gross margins, viewing them as core indicators of a business's fundamental health.

While operating expenses can often be finessed in the short term—by reducing headcount or optimizing various administrative costs—gross margins are a less forgiving metric. If your gross margins are poor, it implies that the basic unit economics of your product are flawed, casting doubts over the entire business model!

On the other hand, a company with bloated OpEx (e.g. Salesforce in 2022) may be criticized as inefficient but isn't fundamentally questioned in the same way. This makes OpEx a secondary concern for many CFOs.

After all, you can defer addressing OpEx inefficiencies, but if your gross margins are suffering—especially in a high-interest rate environment—that's an existential issue requiring immediate action. There's an urgency to improve gross margins, whether by negotiating harder with suppliers or innovating to increase efficiencies, that simply isn't as pressing when it comes to operating expenses.

When you're a supplier whose product falls under the 'cost of revenue' category, as many infrastructure companies do, you're especially vulnerable to price pressures. This vulnerability is amplified if your business model is usage-based, essentially tacking on a flat tax to your customer's revenue— such as Stripe’s 3% payment processing free. In such a landscape, a price war with competitors becomes almost inevitable, as large enterprise customers will shop their contracts around when deciding to purchase or renew. Regardless of any extra features or added value your product may offer, the discussion often boils down to price defensibility. In a high-interest rate environment, where every percentage point in margin counts, suppliers with usage-based models find themselves under heightened scrutiny.

The real crux of the issue isn't the usage-based billing model itself, but rather where that cost lands on a company's income statement. Take Klayvio and Hubspot as examples. Both employ usage-based models but sell into the operating expenses (OpEx), specifically under marketing budgets. These services are not merely expenses; they're tools that can make teams more effective and even drive additional revenue.

In contrast, companies like Datadog and Twilio provide services that are essential for application functionality but are classified as cost of revenue. While invaluable, these services don't directly contribute to revenue generation in the way that a marketing tool might. They're table stakes, necessary for the business to operate but not directly tied to creating additional income. Costs allocated to OpEx—especially those that can arguably help generate more revenue—are scrutinized less harshly than those hitting cost of revenue and affecting gross margins. In a financial landscape where CFOs are laser-focused on gross margins, this distinction becomes crucial.

So, what should infrastructure companies like Twilio and Datadog do? The path forward can be summarized in three strategies: vertical integration, embracing low margins for commodity products, and identifying high-margin upsell opportunities.

First, consider the example of Stripe. The company began with a usage-based payments processing API, a model that inherently exerted pressure on its gross margins. However, Stripe deftly maneuvered this by vertically integrating, adding high-margin products like fraud detection and invoice management to its platform. This diversification not only augmented their revenue streams but also elevated their overall margin profile.

Second, let's look at Costco—a retail giant that operates on razor-thin margins but has managed to turn this into an advantage. By charging a membership fee, Costco has developed a loyal customer base willing to make additional purchases, like vacations and insurance, thus balancing out the low-margin core offerings. Similarly, infrastructure companies can provide indispensable, low-margin services that create stickiness, while finding other high-margin opportunities to upsell.

Lastly, Twilio has provided a template for how to manage a diversified product line that includes both low-margin and high-margin products. The company recently restructured its business into two separate units: one focused on their commodity API products like SMS and Voice, and another on high-margin Customer Data Platform products, such as Segment. By compartmentalizing their offerings in this manner, Twilio can manage costs more efficiently while doubling down on high margin upsell opportunities.

It's important to acknowledge the immense value in becoming the go-to 'primitive' for a building block of the internet. Companies like Twilio and Datadog have built impressive businesses on this very premise, capturing a massive amount of value. However, it's time for a reality check when it comes to the margins of usage-based businesses. While these companies play an indispensable role in the digital infrastructure, the era of unquestioned, high-margin success for usage-based models may be fading. Financial scrutiny, especially in a climate of rising interest rates and margin-focused CFOs, is the new norm.

As the age-old adage goes, 'Your margin is my opportunity.' Companies that pivot strategically—whether through vertical integration, embracing lower margins for commodity products, or identifying high-margin upsell opportunities—will be the ones that continue to thrive. But let's be clear: Thriving doesn't mean perpetuating myths about the financials of usage-based models. It means adapting to the financial realities that govern all businesses, internet-native or otherwise.