📏 Your math doesn’t differentiate you, your worldview does

Everyone is the same…on the surface…

Every investor has Excel. Every buyer has a model. The math is pretty much the same. What’s different, what actually drives outcomes, is a worldview that few share.

We love to feel busy, well-informed, and thorough. But in reality, for many kinds of investments, that busywork has little impact on the ultimate outcome. The thing that separates winners from everyone else isn’t their spreadsheet. It’s how they see the world.

The Illusion of originality in the math

I talk to hundreds of institutional real estate buyers. Almost all of them lead with: “We have a proprietary underwriting model.” Then I see it…and it looks identical to everyone else’s.

Doing this work isn’t bad, it is really important. But it gets you to the starting line, not the finish line.

The danger is mistaking the model for the edge. You start to believe that because “multifamily performed poorly in 2023, all markets performed poorly.” In reality, Indianapolis and several other markets saw rents and property values rise in that same period.

The models rhyme. The differentiation is tiny. The edge comes from interpretation, not the cell references.

Real Estate: same spreadsheet, different bids

I’ve seen the same model lead to radically different decisions:

Buyer A sees commodity apartments in a tired secondary market.

Buyer B sees a secular shift toward Portland spillover and undervalued Southern Maine towns.

Buyer C sees an inflation hedge and capital preservation.

Buyer D sees a platform for operational excellence with tech-enabled NOI expansion.

Same math. Different worldview. Worldview drives the bid — and the return.

Tech parallels

Airbnb — Math: TAM looked laughably small. Worldview: Trust + design could rewire travel.

Stripe — Math: Crowded, low-margin. Worldview: Developers as the new distribution channel.

Tesla — Math: EVs looked niche. Worldview: Cars could be electric and aspirational.

Facebook — Math: Social networks are fads. Worldview: Real-identity networks compound.

Amazon — Math: Unprofitable e-commerce. Worldview: Internet scale would crush margin fears.

Shopify, MongoDB, ServiceTitan, Toast, Snowflake, Nubank — each “too small” or “too risky” on paper; each massive in reality because founders bet on a worldview, not consensus math.

Math is consensus. Worldview is non-consensus.

The spreadsheet makes you feel in control, but it rarely gives you an edge. Everyone can run the same LTV/CAC ratios, cap rates, or DCFs. What separates winners is what they believe when they look at those numbers.

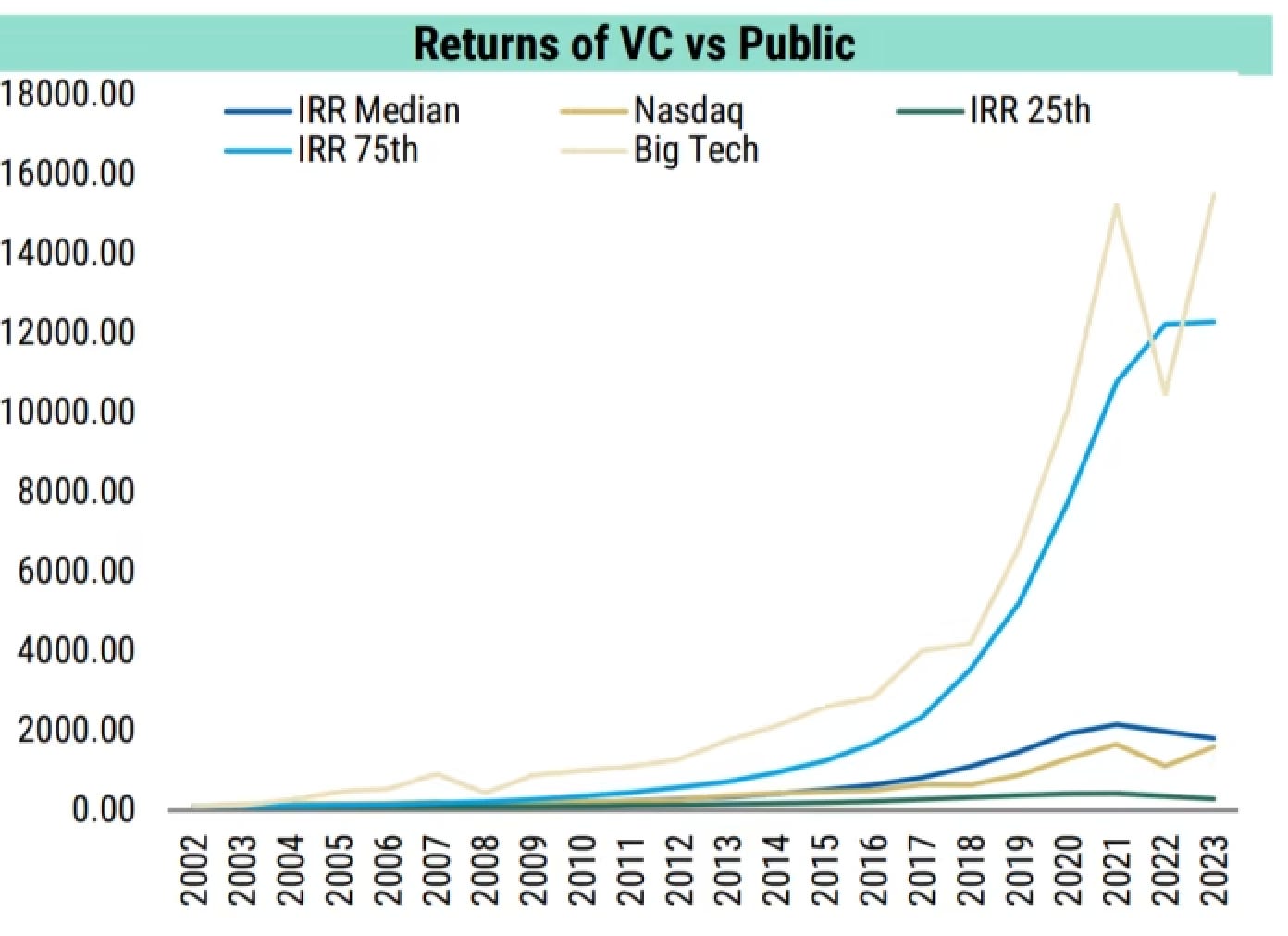

In venture especially, market math is often obviously wrong, but it gives people an excuse to be lazy. Most VCs don’t beat the market for a reason. Doing the work to form a thesis that requires real change in the world is hard.

Closing

In the end, much more of investing, and succeeding in the world, is about gut and grit than we like to admit.

The spreadsheets give us comfort. They make us feel like we’ve turned the future into something repeatable, quantifiable, inevitable. But that’s an illusion.

Every deal, every company, every market inflection comes down to a leap of faith. You either believe in the world as it is, or you see it as it could be. You either stick with the consensus math, or you take the non-consensus worldview that feels just a little insane at the time.

We want to ascribe repeatability to all things. But the truth is: calculated luck, conviction, and the willingness to act when the numbers don’t look perfect are the only ways to actually create something new.

Great writing! Love the tech examples. I guess a great company isn't just about tech/math/autism as you said, there must be a bigger vision/mission!